It’s hard to narrow down a year’s worth of reading to a manageable list of the cream of the crop, but I’ll try. From the books I read in 2016, here are the fifteen books I would most recommend. First are the top three essential books that I would most enthusiastically recommend to anyone. The other twelve were also great, and I recommend them heartily, too. If you want to check out last year’s list, click here. Like last year, I’m putting them in the order that I read them. Unlike last year, I’m including longer excerpts from my reviews to give a fuller recommendation. But if you’d like even more, click on the title of the book for the complete review. Now to the books!

The Top Three

Evicted (Matthew Desmond)

“an essential book. Please, please, read it. Desmond makes the convincing case that there is a serious lack of affordable housing that exacerbates, and is a root cause of, the hardships the poor face. The book follows the lives of a small number of tenants in Milwaukee and their landlords through their evictions and searches for shelter. […] If you have any interest in understanding poverty, please read this book. It is uniformly excellent. I can hardly recommend it enough.”

Kindred (Octavia Butler)

“a visceral novel about slavery in America. It’s 1976, and the narrator Dana, an African American, is somehow transported back to antebellum Maryland where she is confronted with a drowning white child. She travels back and forth, seemingly at whim, until she realizes that she is connected to the child. […] The story takes the jumps in time as a given. One of the strengths of this device is that it puts our modern sensibilities back into the past so that we can better imagine what life was like for slaves and their owners. It’s so easy for me as a white person today to think that I would have of course been an abolitionist if I had lived back then. But what if I had lived in the south where slavery was an institution interwoven into the fabric of everyday life? What if my own family had owned slaves? Would I have really held beliefs that would be to the detriment of my own welfare? It’s a tough question. The book makes us consider that it was the times that made the person. In describing the slave owner, Dana says this, “He wasn’t a monster at all. Just an ordinary man who sometimes did the monstrous things his society said were legal and proper” (134). And she describes many monstrous things that he does. It’s enough to make us weep.”

The Warmth of Other Suns (Isabel Wilkerson)

“an essential work of history. Wilkerson tells the story of the internal migration of millions of black Americans from the rural South to the urban North and West during the 20th century. Actually, she focuses her attention on three individuals as representatives of those millions. […] Throughout these three stories, Wilkerson weaves in all the appropriate context so that we as readers can see the big picture, too. It’s really a marvelous narrative history that illuminates so much of the 20th century and today. I can hardly say enough good about it. Everyone should read it.”

And all the other great ones

Mrs. Dalloway (Virginia Woolf)

“It starts with one of the famous lines of literature: “Mrs. Dalloway said she would buy the flowers herself.” From there, we follow Clarissa Dalloway (and other characters) through all the preparations for a party that evening at her residence. […] The narration floats and glides from character to character, in and out of minds, seamlessly transitioning from one to the next, like a butterfly flitting here and there. It can be disorienting, but it is also so fluid. We get to experience life through so many eyes and minds. It’s exquisite.”

Our List of Solutions (Carrie Oeding)

“a collection of poetry full of longing and insight and barbecues. One thing I noticed is that this collection works as a cohesive book and not merely a random selection of poems by one author. Characters and objects and themes recur throughout the book, filling out the neighborhood feel to the proceedings.”

Sula (Toni Morrison)

“a really great novel. It tells the story of two friends, Sula and Nel, who grow up in a small, segregated Ohio town. In brief chapters the story flows as the two girls share life together and then separate when Sula leaves town to live freely. Nel stays and settles down until the day Sula comes back and shakes things up again. […] I began the book worried that it would be too “literary,” which by itself is not a fault and which I often love about books. I love many difficult literary books. But I’ve found that it’s harder for me to give those kinds of books the attention and concentration required these last few years now that I have kids. I’m more easily distracted. So I loved that I could follow the story in Sula, and it was still a deep and rich book even if not as difficult as I expected. An impressive achievement.”

The Sixth Extinction (Elizabeth Kolbert)

“There have been five major extinction events in Earth’s history, and we are currently living during the sixth. Previous extinction events have been caused by catastrophes like asteroid impacts. Not so for the sixth extinction, which we are currently witnessing. Human behavior, whether greedy or careless, has caused the extinction of untold numbers of species.”

This One Summer (Mariko Tamaki and Jillian Tamaki)

“a touching graphic novel about growing up. It’s the story of Rose, a girl on the cusp of becoming a teenager. Every summer she and her parents travel to a cabin on a lake for vacation. The routines are established: swimming in the lake, bonfires on the beach, reading in her room, and playing with Windy, another girl a year or two younger whose family also comes to the lake every summer. […] The art is a real strength, too. At times cartoony, and other times more detailed and realistic, it’s in total harmony with the story.”

Inspiration and Incarnation (Peter Enns)

“I feel like it is a book that was written for me, a book that helps me make sense of the Bible and modern scholarship at a time when I’m full of questions and doubts. The main thesis of the book is that there is an incarnational analogy between the Bible and Jesus where both are fully divine and fully human. […] I would highly recommend this book to any Christian, especially anyone with an evangelical background who finds themselves asking how modern scholarship on the Old Testament can be reconciled with believing that the Bible is still God’s word.”

The Historian (Elizabeth Kostova)

“a thoroughly engrossing literary thriller. Playing with the historical Vlad the Impaler and Bram Stoker’s character Dracula, the novel follows the investigations of an unnamed narrator, her father, his mentor, and other historians as they try to unravel the mystery of what exactly happened to Dracula and where he is buried. It all starts when the narrator finds a letter in her father’s library, tucked away in a strange book. The letter starts, “My dear and unfortunate successor…” and the book is an ancient volume with totally blank pages except for a woodcut image of a dragon at the very center of the book.”

Does Jesus Really Love Me? (Jeff Chu)

“a fascinating series of snapshots of the American church and how it is currently dealing with LGBTQ issues. Chu spends a year talking to Christians–some gay, some not–all over the country to find out about their experiences. When I first heard about this book, I thought it was going to be mostly a memoir about Chu’s own life. While he does give some autobiography, almost the whole book is given over to other people’s stories. He talks to people with views and experiences all across the spectrum. What I really appreciated is that Chu allows people to talk and give their opinions, really seeing them as individuals, even when he disagrees with them. […] I think any Christian, no matter where they stand on the issue, would profit from hearing the stories of these individuals.”

Thunder & Lightning (Lauren Redniss)

“an extraordinary art book about the science and stories of weather. Melding her skills as an artist with her ability to present research in an interesting way, Redniss has created a unique and fascinating book. Chapters range from the history of lighthouses and fog off Cape Spear in Newfoundland to the shipping of ice from New England to warmer climes all over the world to forest fires in Australia and the American West to the science of weather prognostication especially as practiced by the Old Farmer’s Almanac.”

Love Medicine (Louise Erdrich)

“a beautiful novel spanning several generations of two families on and off the reservation in North Dakota. Through a series of interconnected stories that span at least 50 years, Erdrich introduces the reader to marvelous characters who remain alive long after closing the book.”

The Wordy Shipmates (Sarah Vowell)

“a terrifically fun history lesson on Puritan New England. While not a historian, Vowell has done the research in primary documents to get the story right. […] She loves America and its history, but she’s also willing to looks at its faults and how it has failed to live up to its ideals. I would highly recommend this take on the Puritans. It’s made me want to read more on them in a way no other previous encounter in a history textbook has.”

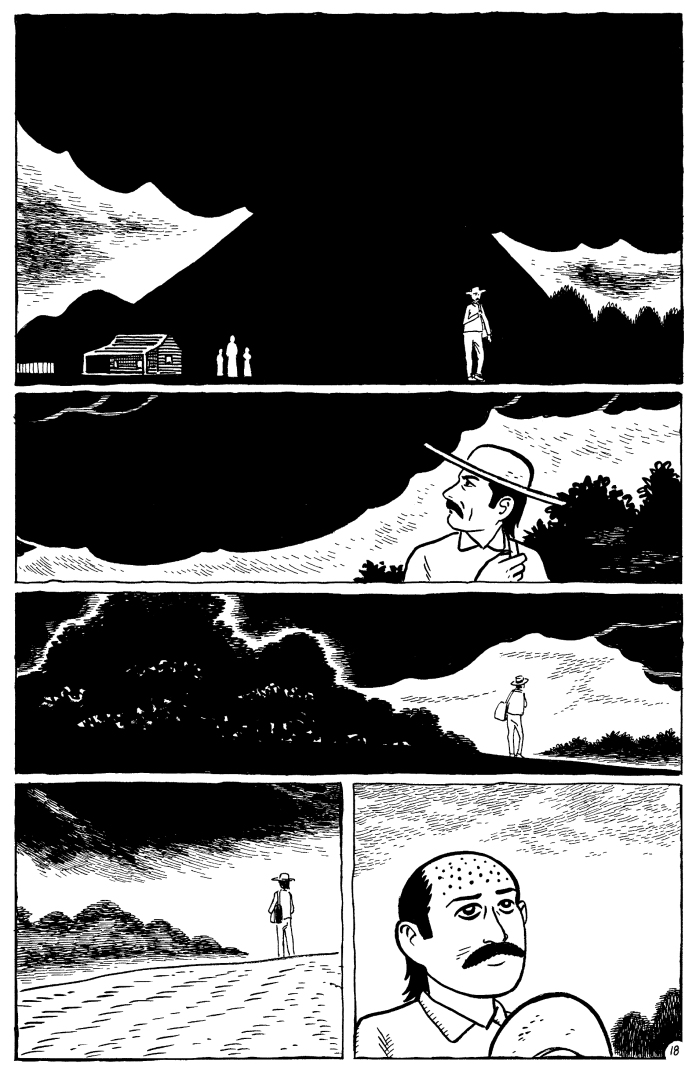

Julio’s Day (Gilbert Hernandez)

“a fascinating look at one man’s life and the life of a century in a graphic novel that is exactly 100 pages long. Julio himself lives to be 100, born in 1900 and dying in 2000. The story of the century is also there, but the focus is on Julio and his family and friends.”

I mentioned in my last set of reviews for 2016 that I don’t plan on doing my monthly roundup of mini book reviews anymore. However, I’ll still do a best books of the year feature of the books I liked and would most recommend. I’m already working on that list. I hope I find as many good ones as this year.